Philosopher Thomas Carlyle famously claimed that “The History of the world is but the Biography of great men.” Given all the hero worship in our culture — especially when it comes to celebrities, or titans of business like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk — it’s clear that many Americans share Carlyle’s perspective.

But what about the opposing view? In War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy wrote that “in historical events great men — so-called — are but labels serving to give a name to the event, and like labels they have the least possible connection with the event itself.”

On the one hand, we have a top down view of history, where events (and the great mass of people) are driven along by the ideas of geniuses like Newton, Napoleon and Einstein.

On the other hand, we have the bottom up view, where “great men” are mostly carried along like surfers on a wave. To be sure, they must possess great skill to ride it, but the wave would have come regardless, and it’s likely that in their absence someone else would have possessed the skill to have ridden it as well.

Historians like Eric Foner and Howard Zinn are good examples of the latter approach. Foner’s Story of American Freedom and his two-volume history of the United States — Give Me Liberty! — focus on themes instead of famous people. And Zinn’s People’s History of the United States focuses on traditionally marginalized people — workers, women, minorities, immigrants and Native Americans — to show how the “great men” of history have just as often been on the wrong side of it.

But even though these more thorough and convincing accounts of history exist, still the myth of genius pervades our culture. How do we account for that? And is there a better way to think about exceptional people that allows us to recognize their contributions without erasing those of others?

Why we fall for the great man theory

In Language, Truth, and Logic, philosopher A.J. Ayer wrote:

It happens to be the case that we cannot, in our language, refer to the sensible properties of a thing without introducing a word or phrase which appears to stand for the thing itself as opposed to anything which may be said about it. And, as a result of this, those who are infected by the primitive superstition that to every name a single real entity must correspond assume that it is necessary to distinguish logically between the thing itself and any, or all, of its sensible properties.

And so they employ the term “substance” to refer to the thing itself. But from the fact that we happen to employ a single word to refer to a thing, and make that word the grammatical subject of the sentences in which we refer to the sensible appearances of the thing, it does not by any means follow that the thing itself is a “simple entity,” or that it cannot be defined in terms of the totality of its appearances. It is true that in talking of “its” appearances we appear to distinguish the thing from the appearances, but that is simply an accident of linguistic usage.

In this passage, Ayer seems to be describing two distinct but related fallacies: the fallacy of reification and the fallacy of essentialism.

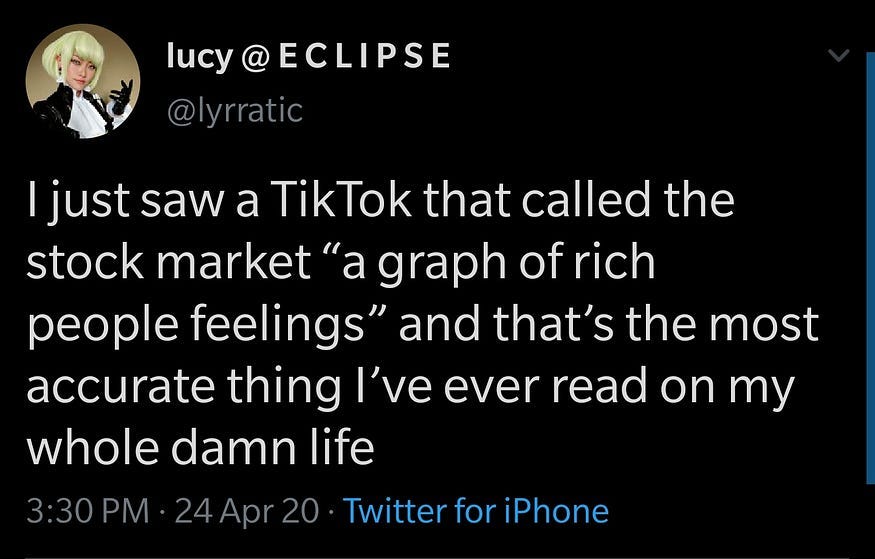

Reification involves confusing some abstract event or process with a concrete thing. For example, if I said the stock market panicked over higher-than-expected unemployment numbers, I would be ascribing the mental state of a concrete being to what is in fact an abstract institution. Collapsing all those businesses, banks, traders and clients into “the stock market” papers over the many differences (including conflicting interests) between them.

Still, reification can be useful if it allows us to draw productive inferences. It can also be quite funny when deployed ironically. Here’s someone using the same example I just gave, but with what we must imagine was a knowing, impish grin.

In contrast to reification, essentialism is about taking a whole bunch of concrete objects and experiences, and distilling them down into an abstract concept or formula. Maybe the most famous example of essentialism is Plato’s theory of Ideas. According to that theory, every tree, river, lion or person is what it is because it partakes of the essence of the eternal Tree, River, Lion, or Person as conceived in the mind of the Creator.

Essentialism can also be useful. It can suggest testable models of nature, deepening our understanding of complex physical or biological processes. The concept of a species in biology is a good example of distilling a whole bunch of individuals into an abstract category. It acts as a predictive tool, helping us better understand why individual lions would behave in predictable ways, for example, while individual gazelles behave in predictably different ways.

Ironically, however, a species is also a good example of how essentialism can lead us astray. When we start to treat species as metaphysically real entities instead of useful abstractions, it makes it very hard to accept the truth that these are just groups of individuals, and that over time the pressures of evolution may cause the descendants of those individuals to look very different, to be members of a different species.

Reification and essentialism differ in the sense that reification takes the abstract and makes it concrete, whereas essentialism takes the concrete and makes it abstract. But they have something very important in common: both are species of reductionism. Both take the complex and attempt to make it simple.

In the case of history, here we also have an incredibly complex catalog of phenomena, which we can’t possibly hope to chronicle in its entirety. That’s where the Great Man theory comes to the rescue. We reify historical forces by situating them in the body of the genius. And we essentialize the genius by making him the avatar of historical trends.

Yet each of these two steps — reification followed by essentializing — involves a simplification. By reducing so much of history’s complexity into a simple personification, we can tell a story built around relatable personalities, rather than impersonal forces. The important thing to remember is that just because the resulting story feels compelling, that doesn’t make it true.

Returning to the surfer metaphor, I think what we’re really admiring when we admire a genius, is the aesthetic beauty of the story we’ve built around him. Yes, the wave would have come, and yes, someone else probably could have ridden it, but the ride is beautiful and exhilarating nonetheless.

Like an “elegant” scientific theory or a well-executed painting, the Great Man account of history seems to offer a parsimonious, harmonious composition in place of a muddled, cacophonous mess.

A better way to think about genius

The Latin word “genius” originally referred to a kind of tutelary spirit, a personification of the individual’s inborn nature. In this sense, a genius was something that everyone possessed, and each person’s genius was different. It was only much later that we came to think of genius as a synonym for extreme general intelligence, something that belonged only to the few.

That shift was unfortunate, for two reasons. First, when a person enjoys success in one domain, the belief that this is attributable to their status as a “genius” supports the inference that their opinions in unrelated domains are entitled to deference as well.

But clearly that’s not the case. Steve Jobs likely could have beaten his cancer if he had heeded his doctors’ suggestion to have surgery. Instead he opted for alternative medicines and juice cleanses. And whatever Elon Musk’s strengths in the area of engineering, he clearly doesn’t know anything about vaccines or epidemiology.

Second, redefining “genius” as “exceptional general intelligence” made it seem natural to separate these individuals from the social context without which they never could have developed and deployed their talents.

We think of a genius as a bright, shining star in the blackness of space. But a better metaphor might be the tip of an iceberg. The most visible aspect of an historical trend is merely that much of it that bobs above the surface. Most of what we call “genius” resides in all those social facts that lie beneath.

Rather than being localized in the “great man,” genius should be thought of as something smeared out across many people. It can be channeled through individuals, but only if the right institutions are in place. A child can be born with a predisposition to develop a high IQ, for example, but if society doesn’t invest in education, public health and the alleviation of poverty, most of those potential IQ points will never materialize.

Conclusion

Fetishizing individual geniuses has one last, pernicious effect. It dupes us into thinking that genius is bestowed rarely and randomly. It lulls us into thinking that we have to wait for Great Men to arrive on the scene and save us from all manner of social, political, economic or technological problems.

But in truth, we can exercise a great deal of control over the conditions that create the waves that genius rides. Eliminating illiteracy, hunger and childhood disease, for example, would create an explosion of genius.

If we believe that genius is a quality of rare and randomly occurring individuals, our duty is to gratefully obey them, our natural masters. But the more we see genius as a trait of societies rather than individuals, the more we realize how much power we have to bring genius into the world, and the easier it will become to do just that.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Truth Evolves to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.